By: Jose Gabriel Abalos, Jarl Tynan Collado, Paola Angela Bañaga, Grace Betito, Zenn Marie Cainglet, Aubrey May De Francisca, Xzann Garry Vincent Topacio, Christine L. Chan, Maria Obiminda Cambaliza, James Bernard Simpas, Genevieve Rose Lorenzo, Melliza Cruz, Connor Stahl, Armin Sorooshian, Nofel Lagrosas, Fr. Jose Ramon Villarin, SJ, and Fr. Daniel McNamara, SJ

Summary:

- Long-term 24-hr PM2.5 measurements show improvements in air quality with “moderate” levels of PM2.5 concentrations for most of the sites compared to “unhealthy” levels the previous year.

- Real-time PM2.5 measurements show a general increase in PM2.5 concentration right after midnight reaching unhealthy levels for some sites.

- Size-segregated PM mass was lower than last year’s New Year, with mass distribution less influenced by firework and traffic emissions due to COVID-19 restrictions.

Introduction:

As a result of the global pandemic that has persisted for almost a year by now, Filipinos needed to welcome the new year a little differently. Since the first cases of COVID-19 were recorded in the country in March 2020, protective health protocols and social distancing measures are strictly being observed in public places such as malls, restaurants, and stores in an attempt to slow its spread. In consideration of a possible surge in new COVID-19 cases from New Year’s Eve celebrations, the local government signed Resolution 19, urging all local government units to ban the use of firecrackers. This resolution also strengthens the President’s Executive Order No. 28, issued in 2017, mandating stricter regulations on the use of firecrackers and confining the use of pyrotechnics for community fireworks displays only. Moreover, only certain types of pyrotechnics were approved to be part of community firework displays during the New Year’s Eve celebration (Rappler, 2020).The festive and colorful Filipino tradition of welcoming the new year with fireworks and firecrackers was strictly prohibited this year to control public gatherings, and was found to be successful in lowering firecracker-related injuries by 85% relative to the previous year: with only 50 cases recorded compared to last year’s 340 (DOH, 2021). Studies also show that exploding fireworks emit hazardous pollutants such as sulfur dioxide (SO2), nitrogen dioxide (NO2), and particulate matter (PM) into the atmosphere, thereby intensifying air pollution levels in a short amount of time (Greven et.al., 2019; Wang et al., 2007). Most of the particulate matter released at these transient pollution events is actually 10 times smaller than a hair strand — small enough to penetrate deep into our lungs and into the bloodstream. By definition, this is known as PM2.5,

particulate matter with a size of 2.5 micrometers or less in diameter (COMEAP, 2006). Exposure to this criteria pollutant, even momentarily, is considered unsafe to everyone, especially to children and elderly, and people with underlying respiratory diseases (Kim et al., 2015).

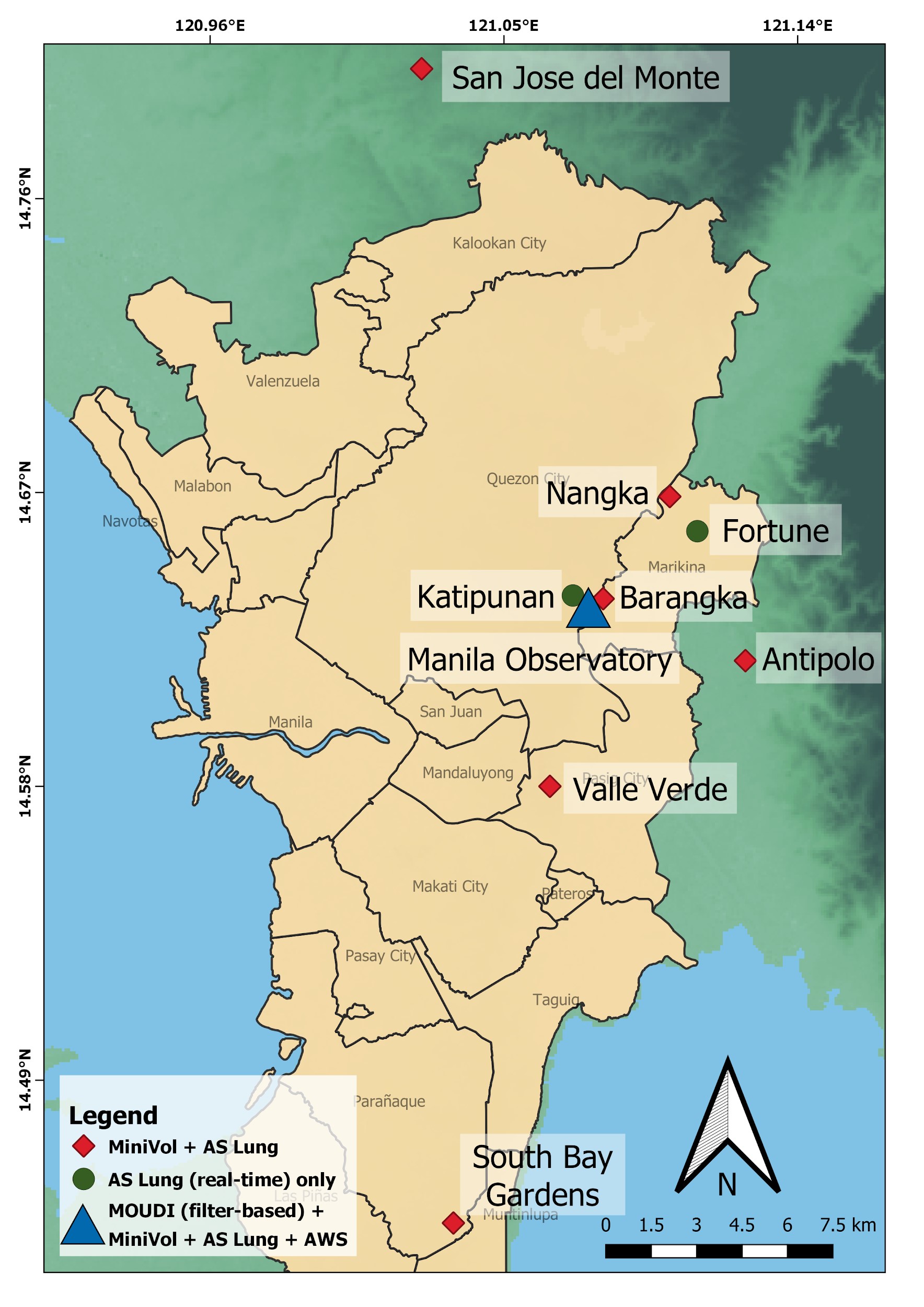

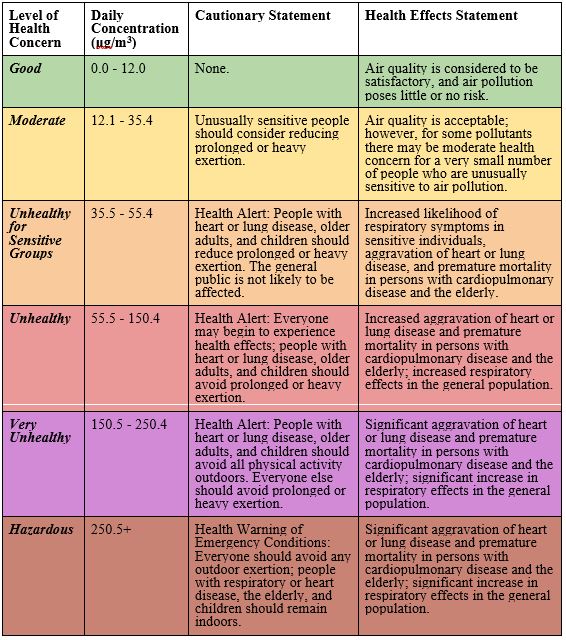

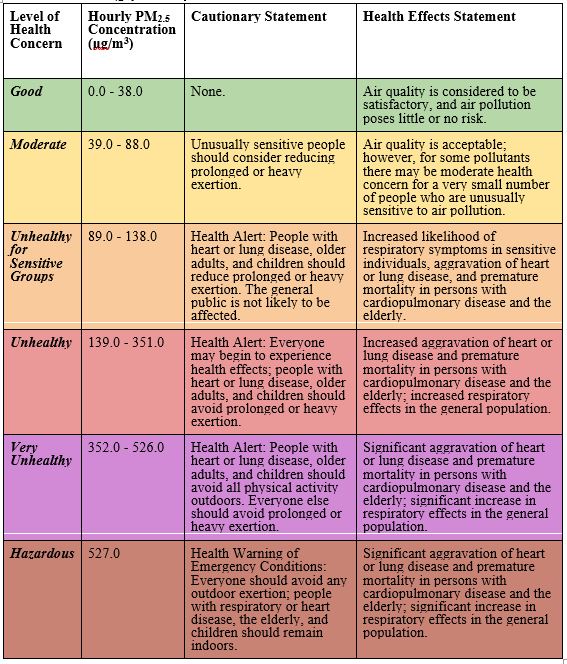

To inform the public about air quality and its effects on susceptible groups, the United States Environmental Protection Agency (US EPA) uses an Air Quality Index (AQI) for PM2.5 and other criteria pollutants. Table 1 shows the US EPA AQI for 24 hours, while Table 2 shows the US EPA AQI for hourly PM2.5 concentration. The Manila Observatory has been monitoring PM2.5 concentrations every New Year since 1998. Filter-based PM2.5 concentrations were collected using a portable MiniVol sampler operating at 5L/min. The samplers were programmed to run from 12:00 p.m. of December 31 to 12:00 p.m. January 1 and were deployed in seven sites across Metro Manila: (1) Manila Observatory, Quezon City; (2) Barangka, Marikina; (3) Nangka, Marikina; (4) Mambugan, Antipolo; (5) Valle Verde, Pasig; (6) South Bay Gardens, Parañaque; and (7) San Jose del Monte, Bulacan. In addition to the deployed filter-based samplers, near real-time PM2.5 concentrations were also collected using the AS-Lung PM2.5 personal samplers. The personal samplers were also deployed in nine sites: (1) Manila Observatory, Quezon City; (2) Barangka, Marikina; (3) Nangka, Marikina; (4) Mambugan, Antipolo; (5) Valle Verde, Pasig; (6) South Bay Gardens, Parañaque; (7) San Jose del Monte, Bulacan; (8) Katipunan Avenue, Quezon City; and (9) Fortune, Marikina. A more in-depth sampling looking at size-segregated PM was collected using a Micro-Orifice Uniform Deposit Impactor (MOUDI) installed at the Manila Observatory.

Figure 1. Particulate matter (PM) filter-based and continuous sampling locations for New Year 2021. The legend indicates the type of instrument used for each site. Minivol samplers for 24-hour sampling were deployed at seven sampling sites: (1) Manila Observatory, Quezon City; (2) Barangka, Marikina; (3) Nangka, Marikina; (4)Mambugan, Antipolo; (5) Valle Verde, Pasig; (6) South Bay Gardens, Parañaque; and (7) San Jose del Monte, Bulacan. AS-Lung personal samplers for real-time continuous sampling were installed at nine sites: (1) Manila Observatory, Quezon City; (2) Barangka, Marikina; (3) Nangka, Marikina; (4) Mambugan, Antipolo; (5) Valle Verde, Pasig; (6) South Bay Gardens, Parañaque; (7) San Jose del Monte, Bulacan; (8) Katipunan Avenue, Quezon City; and (9) Fortune, Marikina. Also installed in Manila Observatory is the University of Arizona’s Micro-Orifice Uniform Deposit Impactor (MOUDI)..

Long-term 24-hr PM2.5 measurements show improvements in air quality with “moderate” levels of PM2.5 concentrations for most of the sites compared to “unhealthy” levels the previous year.

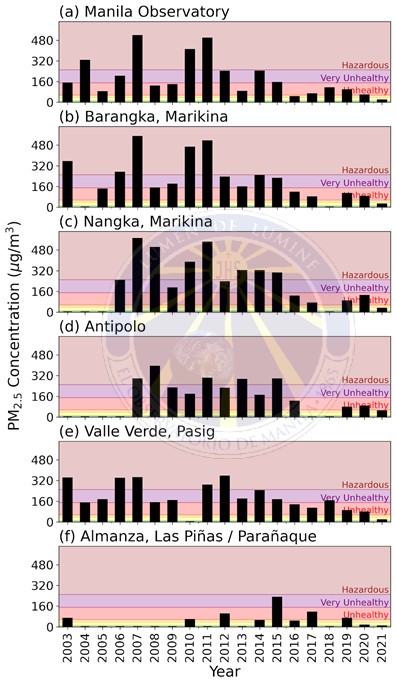

Measurements of PM2.5 concentrations for this year (2021 New Year’s Eve) were significantly lower relative to previous years with concentrations reaching moderate levels (Figure 2). In Parañaque, a residential area, 24-hour PM2.5 concentrations reached the “good” category under the US EPA AQI. It is important to note that these levels signify acceptable air quality conditions, a fitted requirement especially in locations where families, including the elderly and the children, thrive in.There is a sharp decrease in this year’s PM2.5 concentrations in all sampling sites and this observation is primarily attributed to the firework ban and minimized mass gathering protocols during the pandemic (Figure 2). In the figure, it shows Las Piñas (2003-2020) and Parañaque (2021) in the same plot due to proximity of samplers. The PM2.5 levels in Barangka (23 µg/m³), Nangka (27 µg/m³), and Valle Verde (15 µg/m³) improved from “unhealthy” to “moderate” category while PM2.5 concentrations at Manila Observatory improved from “unhealthy to sensitive group” to “moderate” level. Out of the seven sites, the PM level in the “unhealthy for sensitive groups” category (US EPA 24-hour standard) was only registered at Antipolo (47 µg/m³). Compared with last year’s measurements, the decrease in PM levels was highest at Valle Verde, Pasig (5 times lower) followed by Nangka, Marikina (4 times lower), Barangka, Marikina, and Manila Observatory (3 times lower). The notable decrease in PM concentrations compared to the previous year is due to the stricter firework ban imposed during the pandemic. For example, the annual community-based fireworks display in Marikina City was postponed for the safety of the community against the COVID-19 pandemic.

Figure 2. Twenty-four hour average PM2.5 concentrations (μg/m³) during New Year’s from 2003 to 2021. Samples were collected from 12 p.m. 31 December to 12 p.m. 1 January using portable MiniVol samplers at the following sites: (a) Manila Observatory, Quezon City; (b) Barangka, Marikina City; (c) Nangka, Marikina City; (d) Oro Vista Royale(2003-2020)/Mambugan(2021), Antipolo City; and (e) Valle Verde 5, Pasig City; and (f) Almanza, Las Piñas (2003-2020) / South Bay Gardens, Parañaque (2021). The measurements are plotted over the United States Environmental Protection Agency (US EPA) 24-hour PM2.5 Air Quality Index (AQI) (Table 1, Appendix).

Real-time PM2.5 measurements show a general increase in PM2.5 concentration right after midnight reaching unhealthy levels for some sites.

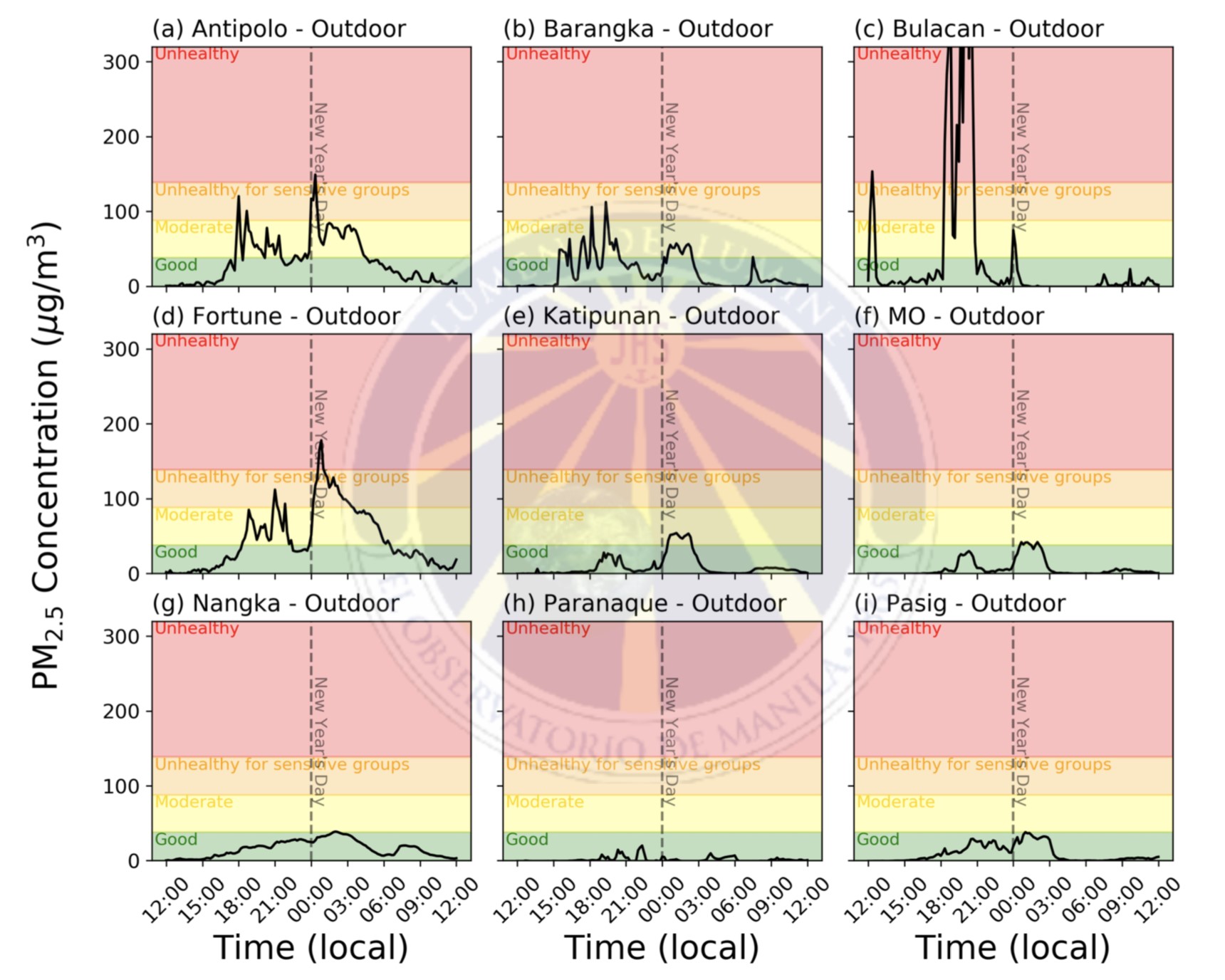

Nine AS-Lung portable sensors were deployed to monitor PM2.5 concentrations at a higher temporal resolution (about 15 seconds). Just like the filter-based samplers, the sensors were made to run from 12:00 p.m. of December 31 to 12:00 p.m. January 1. The dataset was averaged over 10-minute intervals to reduce the noise.

Figure 3. Real-time PM2.5 concentrations (μg/m³) from 12:00 p.m. 31 December 2020 to 12:00 p.m. 1 January 2021 from AS-Lung portable PM2.5 samplers located in (a) Mambugan, Antipolo City; (b) Barangka, Marikina City; (c) San Jose del Monte, Bulacan; (d) Fortune, Marikina City; (e) Katipunan, Quezon City (f) Manila Observatory, Quezon City; (g) Nangka, Marikina City; (h) South Bay Gardens, Parañaque; (i) Valle Verde 5, Pasig City, plotted over the United States Environmental Protection Agency’s (US EPA) Air Quality Index for hourly PM2.5 concentrations (Table 2, Appendix).

For Bulacan, significant large spikes in real-time concentrations are observed at around 12:00 noon and 6:00 p.m. to 10:00 p.m. of December 31, and this observation is attributed to activities such as residential cooking, in preparation for the New Year’s Eve feasts (Figure 3). A similar pattern is also observed in Antipolo, Barangka, and Brgy. Fortune, where concentrations around these times increased up to levels deemed “unhealthy for sensitive groups” (88-138 μg/m³). Although peaks shortly past 12:00 midnight occurred in most locations, levels in Antipolo and Brgy. Fortune reached unhealthy levels (greater than 138 μg/m³). The spikes in concentrations that occur right after midnight are highly attributable to firework activities and vehicles roaming around while racing their engines to create noise. Due to these activities, concentrations in Barangka, Bulacan, and Katipunan reached “moderate” levels (38-88 μg/m³) after midnight, while concentrations in MO, Nangka, and Pasig stayed within “good” levels of PM2.5 (less than 38 μg/m³). Of all the locations, Parañaque maintained the lowest levels of PM2.5 throughout the entire sampling period. By around 6:00 a.m., PM2.5 concentrations in all locations reverted back to “good” levels. Peaks that occurred past midnight in most locations were short-lived, returning to “moderate” and “good” levels after about an hour, with the exception at Brgy. Fortune where concentrations remained above 88 μg/m³ until around 3:00 a.m.

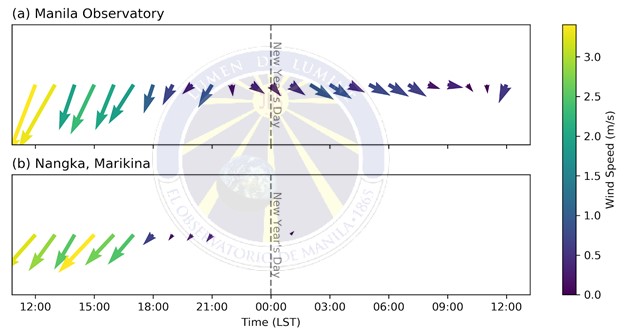

Figure 4. Wind speed and direction (arrows point to the direction where the wind is blowing) at Manila Observatory and Nangka, Marikina from December 31 (12nn) to January 1 (12nn)..

Among the available weather stations to record wind data, two were near the deployed personal samplers. Weather stations at MO and Nangka show mostly northerly winds at both locations (Figure 4). After midnight, the wind was relatively weak, shifting towards the east. The reduced wind speed for this period may have caused stagnation of pollutants from fireworks over the MO and Marikina area. The weather stations recorded no rain during the New Year, implying that there was also no washout of particulates over these areas.

Size-segregated PM mass was lower than last year’s New Year, with mass distribution less influenced by firework and traffic emissions due to COVID-19 restrictions.

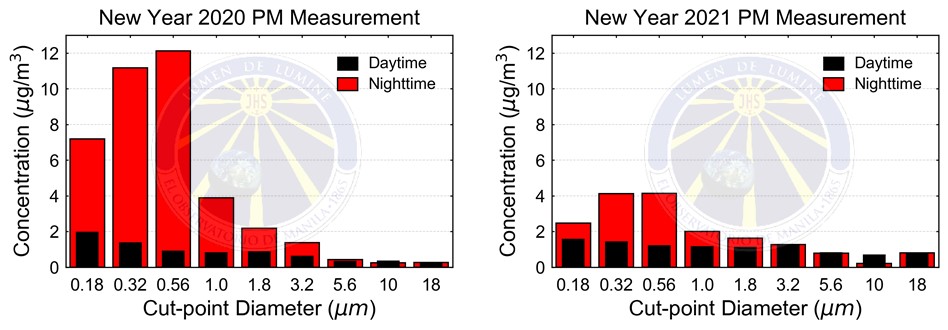

A size-segregated daytime and nighttime PM was also collected this year using a Micro-Orifice Uniform Deposit Impactor (MOUDI) operating at 30L/min at the following aerodynamic cutpoint diameters (Dp): 0.056, 0.10, 0.18, 0.32, 0.56, 1.0, 1.8, 3.2, 5.6, 10, and 18 μm. Only mass concentrations from 0.18 – 18 μm were shown and compared since concentrations for sizes 0.056-0.10 μm were not available last year.

Figure 5. Daytime (31 Dec-02 Jan) and nighttime (31 Dec-03 Jan) mass size distributions of total PM during (left) 2020 New Year’s Day celebration; and (right) 2021 New Year’s Day celebration. Daytime sample collection for 2021(2020) was started at 6:00 a.m. and ended at 5:50 p.m.(5:00 p.m.) while the nighttime sample collection was started at 6:00 p.m. and ended at 5:50 a.m.(5:00 a.m.) (first 2 days) and 6:00 a.m. (third day).

The daytime and nighttime size-segregated PM levels during the 2020 and 2021 New Year’s Days are compared and shown in Figure 5. During both events, nighttime PM concentrations were higher than daytime. This can be driven by temperature differences which affect pollutant dispersion. The higher surface temperature during the day promotes increased mixing from stronger thermal convection, resulting in lower PM levels. During the nighttime, however, a stable, shallower boundary layer is observed, inhibiting particle dispersion resulting in an increase in PM concentration.

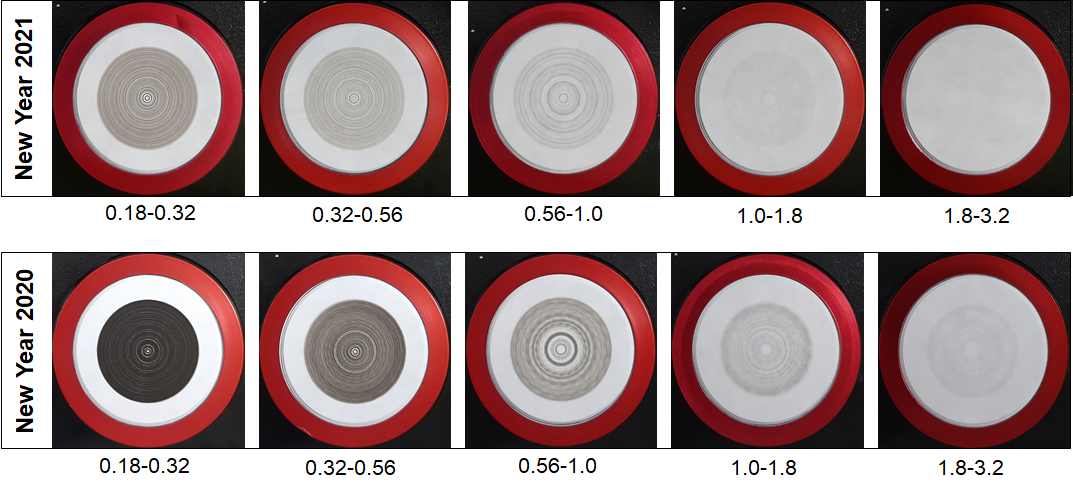

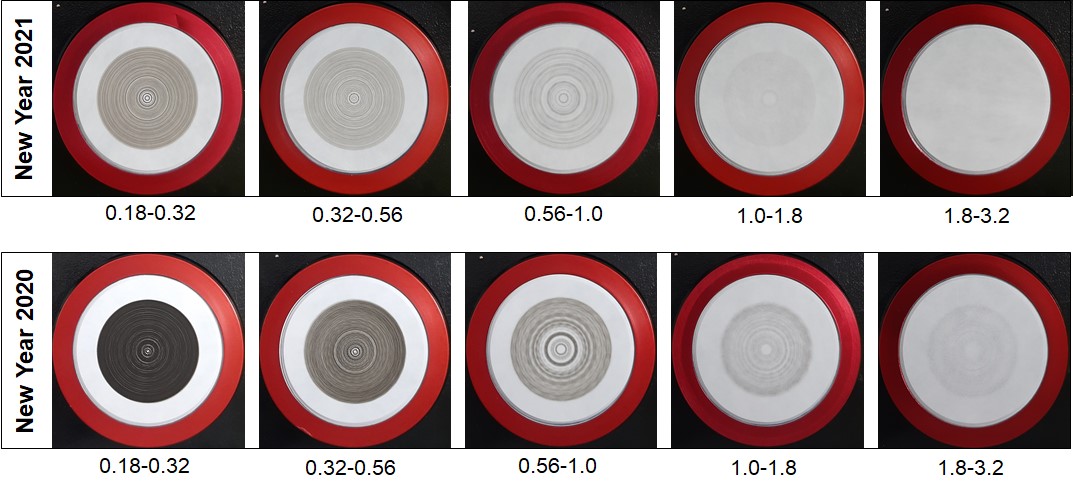

During the 2021 nighttime sampling, the highest peak was observed between 0.56-1.0 μm and the daytime PM peaks between 0.18-0.32 μm. This is similar to what was observed for the New Year 2020 sampling. During firework events, water-soluble species (sulfate, potassium, nitrate, chloride, magnesium) peak in the submicrometer range (0.56-1.0 μm) (Lorenzo et al., submitted). On regular days (figure not shown) without the influence of fireworks, both the nighttime and daytime sample peaks between 0.18-0.32 μm, which is characteristic of the influence of traffic (Cruz et al., 2019). The reduced influence of traffic on the PM loading is clearly seen on the filter images shown in Figure 6. The deposit on the filters collected this 2021 New Year (upper panel) was lighter compared to the same time last year (bottom panel).

Figure 6. Comparison of filter images for selected five cutpoint diameters (μm) of PM collected during the 2021 (upper panel) and 2020 (lower panel) New Year celebrations.

Large differences (2-3 times lower) were observed between the PM concentrations in the two successive years especially in the submicrometer range (0.18-1.0 μm). This observation is again likely due to firework bans implemented in cities in Metro Manila and cancellations of community-based firework displays to avoid mass gatherings during the pandemic. In addition, less traffic was also observed since the majority of workers are still working from home. Shopping malls and other business establishments were likewise only open for a limited number of hours.

In summary, this year’s New Year’s Eve celebration was drastically different due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Compared to previous years, protocols implemented to slow the spread of COVID-19, along with strict enforcement of the fireworks bans, have significantly contributed to the reduced pollution levels observed this year; no sites registered dangerous levels of pollution typical of New Year’s Eve celebrations from previous years.

Appendix

Table 1. US EPA AQI for 24-hour PM2.5 concentrations.

Table 2. US EPA AQI for hourly PM2.5 concentrations.

References

Cruz, M. T., Banaga, P. A., Betito, G., Braun, R. A., Stahl, C., Aghdam, M. A., Cambaliza, M. O., Dadashazar, H., Hilario, M. R., Lorenzo, G. R., Ma, L., MacDonald, A. B., Pabroa, P. C., Yee, J. R., Simpas, J. B., & Sorooshian, A. (2019). Size-resolved composition and morphology of particulate matter during the southwest monsoon in Metro Manila, Philippines. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics, 19(16), 10675-10696. doi:10.5194/acp-19-10675-2019.

Greven, F., Vonk, J., Fischer, P., Duijm, F., Vink, N., Brunekreef, B. (2019). Air Pollution during New Year’s fireworks and daily mortality in the Netherlands. Nature Scientific Reports 9: 5735 (2019). Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-42080-6

Kim, K.H., Kabir, E., and Kabir, S., 2015. A review on the human health impact of airborne particulate matter. Environment International, Vol. 74, pp. 136-143.

Lorenzo, G. R., Bañaga, P. A., Cambaliza, M. O., Cruz, M. T., Azadi Agdham, M., Arellano, A., Betito, G., Braun, R., Corral, A. F., Dadashazar, H., Edwards, E.-L., Eloranta, E., Holz, R., Leung, G., Ma, L., MacDonald, A. B., Simpas, J. B., Stahl, C., Visaga, S. M., and Sorooshian, A.: Measurement report: Fireworks impacts on air quality in Metro Manila, Philippines during the 2019 New Year revelry, Atmos. Chem. Phys. Discuss. [preprint], https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-2020-1028, in review, 2020.

Manila Bulletin. (2020, November 29). Nograles: Christmas get-togethers limited to 10 people in GCQ areas. Retrieved from: https://mb.com.ph/2020/11/29/nograles-christmas-get-togethers-limited-to-10-people-in-gcq-areas/

Philippine Star (2021, January 2). DOH: Firecracker Injuries down to 85%. Retrieved from: https://www.philstar.com/headlines/2021/01/02/2067599/doh-firecracker-injuries-down-85

Philippine News Agency (2021, January 1) DOH Reports 85% decrease in firework injuries for 2021. Retrieved from: https://www.pna.gov.ph/articles/1126103

Rappler. (2020, December 26). Fireworks to welcome 2021? What’s allowed, not allowed [News Report]. Rappler. Retrieved from:

https://www.rappler.com/nation/guidelines-fireworks-new-year-philippines-2021

Wang, Y., Zhuanga, G., Xua, C., and An, Z. (2007). The air pollution caused by the burning of fireworks during the lantern festival in Beijing. Atmospheric Environment 41 (2007) 417–431. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2006.07.043.